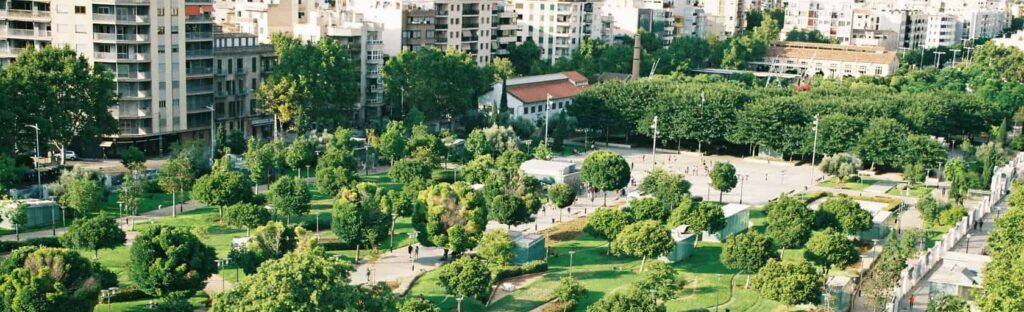

Cities are undoubtedly the habitat of the future: by 2030, two-thirds of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas. However, they are also the main driver of global warming and the places “where the fight for a green recovery will be won or lost”, as they consume 78% of the world’s energy and produce more than 60% of greenhouse gas emissions, according to UN Habitat.

We agree with the WWF that “nature must be at the heart of our cities”. Urban areas are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change: “Globally, 80% of cities face extreme climate-related events”.

Photo: Benjamin from Unsplash

More Green in the City?!

Unfortunately, increasing soil sealing and densification make it challenging to plant more desirable greenery to bind emissions at the source and mitigate heating. Planting trees in urban areas is becoming increasingly difficult. The soil is often sealed, crisscrossed with cables, or tunneled, making it unsuitable for tree planting.

To ensure newly planted trees thrive, adequate root space, water, air, and light must be available. Many tree species grow in nurseries for about 8-10 years before being transplanted into cities, where they take several more years to develop large, shade-providing canopies. Some of the “well-known ecosystem services of trees [come] into play only in older stages”.

A stately street tree, about 20 years old, is estimated to be worth around €66,000. A newly planted street tree costs approximately €5,000. Many trees in our cities are so stressed by extreme weather, pests, and vandalism that they have to be felled prematurely. In numerous cities, replanting targets are not met due to a lack of suitable spaces. There are mainly two major problems with compensation or replanting: finding the right location and the necessary funds for expensive young trees, as “a young tree indeed costs a lot of money: four-figure amounts are incurred in the first years”.

As reported by Deutschlandfunk , several factors contribute to the threat to the tree population:

- Climate Change: The warmer it gets, the harder it is for trees. More trees in the city would also protect the tree population itself. For new plantings, robust climate trees that can better withstand heat and low water levels are now being chosen.

- Globalization: New pests arrive that plants and trees often cannot adapt to quickly enough.

- Human Activity: Trees are still being felled to make space for new housing or commercial properties.

Photo: Sylas Boesten from Unsplash

“Native” Green in the City?

Furthermore, existing urban greenery suffers greatly, especially “native trees are increasingly struggling” in terms of both care and selection of new plantings. Vibration and fine dust pollution from traffic, space constraints due to compacted soil and various pipelines, road salt, and damage from vehicles or construction work all take their toll. They suffer from climate change with “water shortages and long dry periods”, losing substance and resilience. “Valuable old trees are particularly affected by damage following extreme weather phenomena in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020”. Since the extreme drought and heat periods, there have been “unprecedented levels” of dying trees, according to the “Park Damage Report” by the Technical University (TU) of Berlin, funded by the German Federal Environmental Foundation (Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt, DBU). It documented “branch breaks, collapses, and uprootings of individual trees”, as well as “die-offs of entire groups and stands of trees”. In Berlin’s Schönhausen Palace Park, “there are no healthy trees left”.

The continuous temperature records, the “hottest months on record”, and overall climate change are “taking an increasing toll on trees”, both young and old. The Park Damage Report clearly notes “a deterioration of the situation for trees in recent years”: “59% of all trees are in poor condition”, and “damaged trees have been found in all parks“. The MDR recently headlined the “Forest Condition Report for 2023” („Waldzustandsberichts für 2023“),” presented by Agriculture Minister Cem Özdemir, with “Only one in five trees in Germany is healthy”.

In Berlin, the BUND Berlin stated in 2021 that “the condition of Berlin’s street trees has continued to deteriorate”, calling it a “creeping environmental disaster”, which an analysis by the Senate Department confirmed: “more than every second tree is damaged”. Even a tree considered “a tree of the future” and “a robust city tree” 15 years ago, such as the ash tree, is now facing issues due to a fungus introduced from China.

However, it is not only extreme heat, insufficient water, and improper care that are stressing city trees. In winter, Würzburg’s garden department warned of falling branches and toppling trees due to existing snow loads. The age of the trees or park usage also contribute to their poor condition. City trees are increasingly stressed by heat and drought, with urban temperatures 5-8 degrees higher than in forests, causing them to evaporate more water. This additional water demand cannot be met due to soil sealing. The “extremely dense soil” also means “no room for extensive root systems”. New pests exacerbated by climate change also contribute to faster tree aging: “Street trees often only live for 60 years”.

Young trees planted to positively impact the urban climate also face challenges. It has been observed that young trees tend to die more often near busy streets, not only due to climate change but especially due to “vibrations caused by traffic” that further compact the soil and damage fine roots. Vienna also reports issues with harmful salt use at public transport stops in winter.

Alarmingly, “the overall health of plants is declining“. Some municipalities face “an almost unsolvable task”.

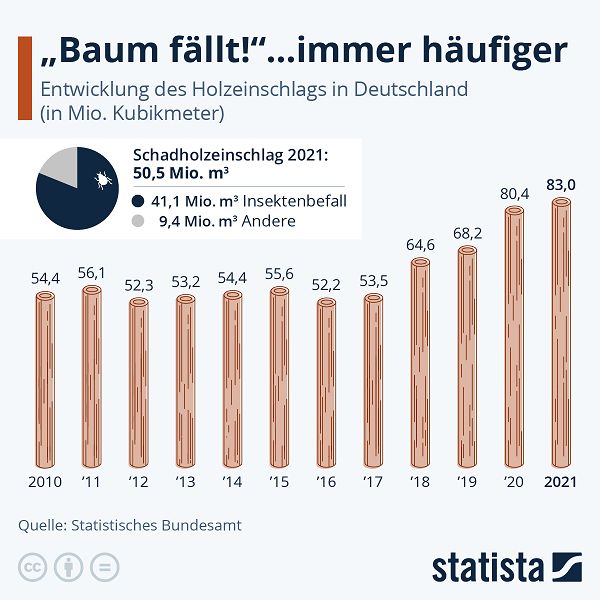

Photos: Henry Perks from Unsplash, Statista

The Solution?

Alternatives are needed. In the future, criteria for future trees will be sought based on “growth strength, life expectancy, maintenance requirements, resilience, and fracture resistance“. “Non-native future tree species, i.e., species favored for climate change in Germany“, generally performed better than native species, particularly concerning “heat stress and drought”. “In general, the greater the biological diversity, the more resilient the forest is, the more resistant it is to pests and diseases“.

However, “exotic” tree species also carry risks, such as (previously) unknown “diseases or pests” or new pollen and allergies.

The World Economic Forum pointed out that “nature is the most resource-efficient solution for creating resilient, vibrant, and future-proof cities“. Examples from around the world show that nature-based solutions can improve the sustainability, resilience, and quality of life in cities cost-effectively and elegantly (International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Nature-based solutions in urban areas can “address a wide range of challenges, including climate change, biodiversity loss, disaster risks, water and food security, human health, and socio-economic development.”

Additionally, a “groundbreaking study” by the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) in 2021 found that “using nature in infrastructure projects could save $248 billion per year”.

Research has shown that:

- “Nature-based infrastructure, also known as ‘NBI,’ costs about 50% less than equivalent built infrastructure while delivering the same – or better – outcomes. In addition to lower initial costs, NBI tends to be more cost-effective in maintenance and more resilient to climate change.”

- “Globally, approximately $4.29 trillion is needed annually for infrastructure, and 11% of this could be met with NBI. This leads to potential savings of $248 billion per year.”

- “Besides cost savings, NBI generates an average of 28% more value than built infrastructure. This is because it provides environmental benefits such as reducing air pollution or capturing and storing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere; social benefits like pleasant relaxation spaces; or economic benefits like promoting tourism.”

- “NBI can deliver savings and benefits across all infrastructure sectors,” including: Approximately 50% of the needs for climate-resilient infrastructure to combat erosion and flood risks and “10% of the needs for transportation infrastructure can be met with NBI such as swales and wetlands that retain and slow down water to reduce flood damage to roads and railways.”

What do nature-based solutions look like?

They are not a single measure but many different ones! There are also differences between nature-based, nature-derived, and nature-inspired solutions. NBS use the “tools that nature already provides”: they often enhance “existing natural or human-made infrastructure and promote long-term economic, social, and environmental benefits“. This includes green infrastructure, soil conservation and regeneration, protecting settlements from floods and seawater, promoting biodiversity and its services, revitalizing places and connecting communities, and improving air quality and lowering temperatures in our cities.

NBS are based on a “simple – and old – idea”, reports Ruth Larbey for the „Economics Observatory (ECO)“.

Photo: Nerea Marti Sesarino

Moss as an Effective Nature-Based Solution for Cities

What could be simpler and older than the oldest land plants on Earth at 450 million years old?

In her article, Ruth Larney also reports on moss – and on us – because our solution comes from nature: specialized, living mosses with their ability to bind and metabolize pollutants and cool the environment through water evaporation offer a real alternative to conventional (urban) greenery.

Photos: GCS

Urban areas have tremendous potential on their surfaces to combat climate change. Moss can actively fight climate change and mitigate its effects. Therefore, we are convinced: Moss must come to the city.

Two key features make moss especially important allies in the fight against global warming: air cooling and purification. Additionally, mosses are like small sponges. Since they only draw water from the air, they are adept at absorbing and storing a large amount of moisture. Moss can store and evaporate up to 20 times its own weight in water. This evaporation results in significant cooling of the air.

These natural properties are maximized using cutting-edge IoT technology and innovative ventilation and irrigation techniques: on a small footprint, approximately 50 watts of electrical power can generate up to 6,500 watts of cooling power—equivalent to the cooling effect of 80-100 newly planted street trees. The particulate filter effect of moss is about ten times higher than that of traditional greenery. On hot summer days, the moss surface can be up to 10 Kelvin (°C) cooler than the surrounding environment, making it an effective solution for combating urban heat islands.

Photo: Stadt Griesheim

Greening measures are often cheaper as standalone actions, with urban tree planting costing at least €5,000. However, space is required, and individual measures do not provide immediate, measurable effects. For example, the CityTree delivers the performance of 81 trees, resulting in approximately 90% cost savings.

Compared to technical filters with similar performance, the initial costs for a CityTree are slightly higher. However, over a five-year usage period, they are about 20% cheaper overall due to the regenerative filter material and lower electricity consumption compared to a combination of air filter and air conditioning.

The fresh air concepts combine sustainability, climate protection, and digitization, and are often eligible for funding by municipalities and businesses. Green City Solutions offers financing, rental, and leasing options with attractive offers. Contact us at info@mygcs.de for more information.

The moss modules are used in various multifunctional fresh air concepts. The integration of traditional green elements to promote biodiversity, analog and digital information tools, seating, water tanks, and even network technology or charging infrastructure allows versatile applications, such as in rainwater management strategies due to their high evaporation capacity.

The moss filters thus contribute to more sustainability and a healthy, livable city — visible and measurable, locally and immediately.

Photo: GCS

We Love Trees

Trees are fantastic, and we all want more of them in the city. (If you want to see how we planted new trees around our headquarters in Bestensee for the tenth anniversary of Green City Solutions, we recommend “A Decade of Green City Solutions — Ten Years for the Best Possible City of Tomorrow”.)

Trees and moss have coexisted for millions of years, providing valuable environmental services such as shading, evaporative cooling, and other vital functions like pollutant and CO2 storage, oxygen production, noise reduction, and contributions to water management. Moss and the fine dust filtered through it even formed the foundation for higher plants like trees. We support this symbiosis in the city!

We see our products as complementary to existing greenery, such as trees, not as replacements!

While a tree is a long-term measure, moss filters provide full performance immediately upon installation, also offering short-term effects.

The intelligent moss filters can also help support existing greenery by increasing humidity and moderating temperatures, potentially reducing failure rates. The significant advantage of moss filters is their ability to operate where trees struggle. A healthy tree requires roughly the same root space as its canopy size—a space that is often unavailable in sealed urban areas with underground shafts, pipes, and cables. Thus, moss filters can function effectively where sustainable, healthy trees cannot find space.

Urban street trees and moss filters do not compete but rather complement each other as solutions for different problems. The perfect symbiosis, both literally and figuratively.

Photos: GCS & Olena Bohovyk from Unsplash

Moss Must Come to the City

The cleansing and cooling effect is particularly valuable where heat and particulate pollution are high, and where many people are present: busy (shopping) streets and squares in city centers, schoolyards, or kindergartens, as well as commercial areas, office workplaces, atriums, shopping centers, train stations, and airports. In these places, moss filters can clean the air and create fresh air zones and meeting places for people.

It would not make sense to try to clean the air of an entire city — billions of cubic meters of air move within seconds, and pollutants are brought in from near and far. Many places in the city have acceptable air quality, or where people do not actually spend time. Important for the future is to create green corridors and areas in cities that ensure fresh and clean air, strengthen biodiversity, and benefit water management.